This week regular blogger Phil Thomas introduces us to the fine art of reading the historic landscape – something that will bring a whole new dimension to your rambles…

It’s easy to be swept away by North Wales’s beautiful landscapes. From rock-splintered Snowdonia to the grass-waving hush of the high Denbigh and Migneint Moors, big views are everywhere. They’re easy to admire, but at the same time it’s easy to miss other things.

Is that a boulder, or a standing stone? Is that pile of rocks just that, or the remains of a burial chamber? And is the path you’re on a route for tourists, or have people and livestock trodden this route for hundreds, if not thousands of years?

Every landscape has a hidden history, and in North Wales there is history everywhere you look. In this, the first of three posts, we’ll share with you the history behind the landscapes – things to look out for while enjoying the great outdoors here in North Wales.

Burial mounds and cromlechs

The oldest visible things in the UK are long barrows, or burial mounds, dating back more than 6,000 years from the Neolithic era. Where there’s good soil, these tended to be earth mounds.

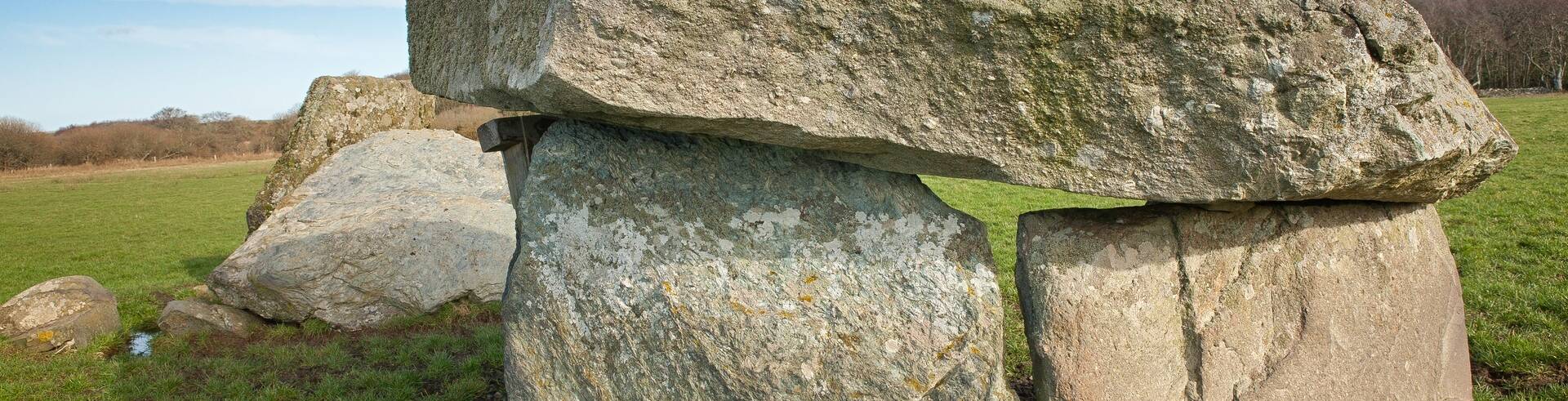

Here in North Wales, the more common type of long barrow is the long cairn or chambered cairn (tomb), the construction of which involved the use of stone. The biggest stones, called megaliths, are the stones we see left standing today. In Wales, we call the megaliths left from chambered tombs cromlechs. Elsewhere in England they’re referred to as dolmens, or quoits in the South West.

There are no fewer than six fascinating cromlechs you can visit on Anglesey. At Bryn Celli Ddu outside the village of Llanddaniel and Barclodiad y Gawres near Aberffraw, the cromlechs are still covered by earth. The latter would once have been 27 metres in diameter.

The other cromlechs have lost their earth mounds. You’ll find them at Bodowyr (near Brynsiencyn) and Lligwy (near an ancient settlement of the same name – more of this in part 3). Presaddfed burial chamber, near Bodedern, is actually thought to be the remains of two burial chambers close to each other. Finally, Trefignath (off the A55 near Holyhead) is believed to have been constructed in three separate phases.

On the mainland, you’ll find cromlechs near Capel Garmon, a hamlet in the hills above Conwy Valley near Betws-y-Coed, and above Rowen on a track leading to Bwlch y Ddeufaen mountain pass (Maen y Bardd).

On the Llyn Peninsula, Tan y Muriau on Mynydd Rhiw high above Porth Neigwl (Hell’s Mouth) incorporates two burial chambers. Around 3,000 BC the tomb was modified to include a long burial chamber in a style found in the area between Oxford and Bristol, a fact neither historians nor archaeologists can satisfactorily explain! To visit Tan y Muriau please ask permission at the farm of the same name, as it’s on their land.

Also on the Llyn is Mynydd Cefn Amlwch, near Tudweiliog village and along the same coast towards Caernarfon is Bachwen, in a field between Clynnog Fawr village and the sea. Bachwen’s capstone (the big flat stone across the top of the supporting megaliths) is covered with so-called cup-marks, thought to have religious or spiritual significance. There are cup marks on a rocky outcrop near Cist Cerrig, another burial chamber between Borth-y-Gest near Porthmadog and the main A497 Pwllheli road.

Finally, the Carneddau mountains translate to ‘the cairns’. They boast more than 20 cairns, thought to date from the Bronze Age (2300–800 BC) and are believed to be tombs.

Hillforts, forts, and motte-and-baileys

There are more than 1,000 Iron Age hillforts in Wales, more per square mile than anywhere else in the UK. We’re not really sure what they were used for, despite the name.

Yes, they are found on hill tops which make naturally defensive positions, so the idea that they were places of refuge is the most common. They could have also been social centres, or even built in prominent locations as symbols of power or status. For the most part, people would have lived on farms on the lower plains.

The hillforts in North Wales are known for their impressive ramparts, often because they were constructed of stone and therefore some are relatively well preserved.

Tre’r Ceiri hillfort near Nefyn is probably the best example, featuring massive dry-stone walls and no fewer than 150 stone roundhouses across its vast interior.

Other good examples include nearby Carn Pentyrch and Garn Boduan, and Caer y Twr on Holyhead Mountain. The Clywdian Range in the east features some prominent examples, including Moel Arthur and Penycloddiau.

Not all forts date from the Iron Age, and not all occupy an obvious hill location.

Tomen y Mur is a Roman fort near Trawsfynydd. You’ll need a map to find it as there are no signs from the main A470. The lumps and bumps near the small car park are the remains of an amphitheatre, while others show where a parade ground once was. In fact, Tomen y Mur is regarded as one of the most complete Roman military sites in Britain – but you do need your imagination to picture it!

Just north of Beaumaris on Anglesey, between the town and Penmon point and its lighthouse, is Castell Aberlleiniog, a fine example of a motte. You can either park by the beach or in Llangoed village car park – from either point you are 200 metres from the reserve which contains this hidden gem.

Nearer to Llanberis is a coastal hillfort at Dinas Dinlle. Although it’s been eroded by the sea, it’s still possible to make out the ramparts on three sides. Roman coins have been found here. Head towards Beddgelert and you can walk up Dinas Emrys, though little remains of its hillfort.

The ubiquitous tumulus…

Look on an Ordnance Survey map of Great Britain…anywhere in Great Britain…and you’ll see a tumulus marked. Tumuli (to give the plural of tumulus its correct name) are everywhere. What looks like an innocuous mound in a field could be a tumulus. Simply put, a tumulus is a mound of earth and stones concealing a grave.

They date from the Bronze Age. Archaeologists have counted at least 20,000 of them in Britain and a good share of them can be found in North Wales. Most of them appear as an upturned dish and are known as bowl barrows.

Off the B5109 near Pentraeth on Anglesey you can see a series of low tumulus, close to a standing stone. While pieces of pottery and other artefacts have been found here, their relationship with the stone (if any) remains a mystery.

Yet the greatest tumulus of all might be one found more the 3,500 feet above sea level. Snowdon, in Welsh, is Yr Wyddfa which approximately translates to ‘the barrow’ or, yes, you guessed it, the tumulus.

Legend has it that a giant called Rhitta Gawr, slain by King Arthur, is buried here. Something to think about when you reach the summit and touch the trig point!

So next time you’re taking in the splendid North Wales views and marvelling at the landscape, take a closer look. Are those lumps and bumps just hills, or something a little more interesting?

Great resources for finding interesting history in the landscapes include Cadw, Our Heritage site for Snowdonia (including the Llyn Peninsula), and the community-led website Megalithic Portal.

In part two of this series – coming in May – we’ll be looking at stones – standing stones and stone circles, more precisely!